LAKE GEORGE — During a stretch of unusually warm weather and calm water last fall, a pair of algal blooms appeared on the famously pristine surface of “the Queen of American Lakes.”

The blooms in Bolton Landing and Assembly Point were the first documented harmful algae, or cyanobacteria, outbreaks on the lake, and they’ve raised urgent questions about whether state officials are doing enough to keep pollution out of its waters.

This sort of bloom is unsightly — flare-ups can resemble green dots, spilled paint or pea soup. The kind spotted around Assembly Point can also become dangerous if they release chemicals that damage kidneys, liver or the nervous system. Tests did not find detectable levels of these toxins.

Other waters, including nearby Lake Champlain, have endured repeated algal blooms apparently caused by pollution. The combination of undrinkable water, worried tourists and lower property values is a nightmare for lakeside communities.

Carol Collins saw Lake George’s first documented bloom near her home on Assembly Point. The stuff she saw in the water is of the same species she did her doctoral research on decades ago.

“It’s sad for Lake George, but it’s not something we didn’t expect,” Collins said.

1of5

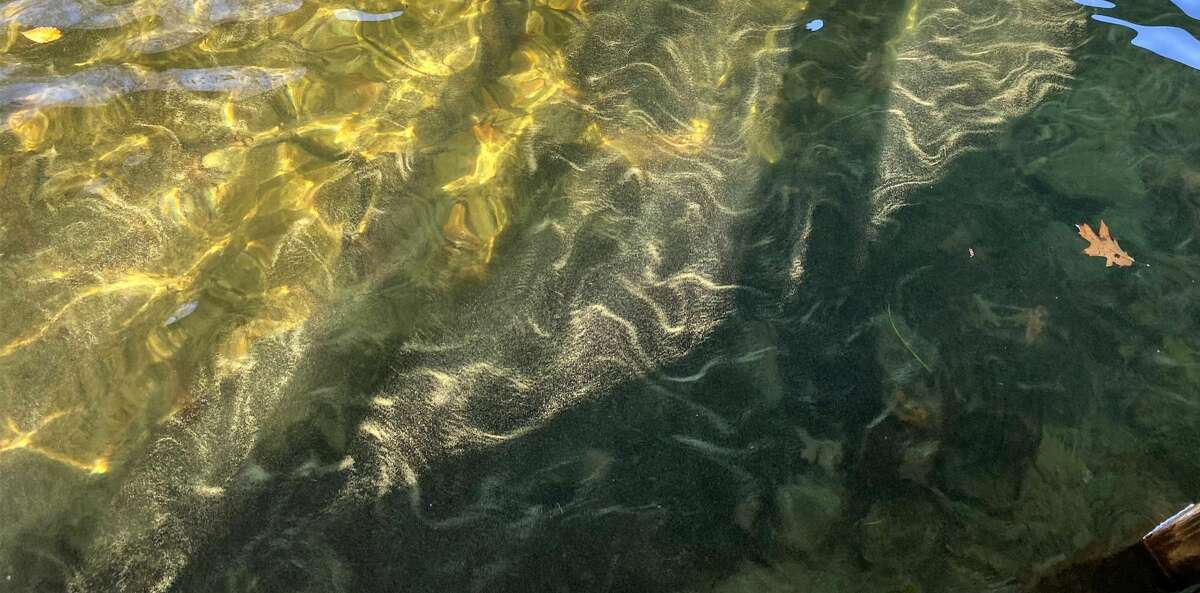

Two sections of Lake George grappled with algal blooms in the fall of 2020. (Photo courtesy Adirondack Explorer)

Adirondack Explorer 2of5

2of5

Two sections of Lake George grappled with algal blooms in the fall of 2020. (Photo courtesy Adirondack Explorer)

Adirondack Explorer3of5 4of5

4of5

Two sections of Lake George grappled with algal blooms in the fall of 2020. (Photo courtesy Adirondack Explorer)

Adirondack Explorer5of5

She wasn’t alone in fretting. And like other researchers, property owners and formerly regulation-weary elected officials, she thinks she knows where to point a finger: leaking lakeside septic systems.

A string of studies over at least the past half-century has warned about septic tank sewage polluting the lake. Some of the same studies showed leaking sewage could cause or contribute to algal blooms. But the state has done little to rein in failing shoreline septics.

In the late 1980s, state lawmakers aware of these worries beefed up the Lake George Park Commission and tasked it specifically with controlling the amount of sewage going into the lake. But some 30 years later, the Park Commission doesn’t have a single person working for it that regulates wastewater.

Collins and other residents, as well as the lake’s two largest nonprofit watchdogs — the Lake George Association and the Fund for Lake George, which recently announced they would merge — have argued that the state has stayed on the sidelines for far too long.

Over the past several years, the state has had to close Million Dollar Beach for days after finding waterborne human bacteria, including E. coli. Officials could never pinpoint what caused the problems, though an aging village sewer system in Lake George, stormwater runoff and leaking septics were all suspects.

And for well over a century, lakeside sanitation has worried people who live around the lake. The Lake George Association, formed 130 years ago, had discussions in the 1890s about sanitation woes. At one point, it hired its own inspector, Harry Smith, to look after the lake. Way back in 1929, Smith was fielding complaints about sewage. One doctor with property on the lake wrote to Smith to complain that another doctor with property on the lake had an outhouse “altogether too close to the brook.”

Perhaps little has changed since then: Recent tests by the association show small levels of caffeine and the chemical sweetener sold as Splenda are in the lake. That indicates sewage is still getting in.

But now, with 6,000 septic systems around the lake, it’s not so easy to point the finger at a single source.

Lake George’s decades-old designation as a park within the Adirondack Forest Preserve started to really mean something in the late 1980s when lawmakers decided to give more power to the Lake George Park Commission.

Bill Hennessy, an Albany insider and ally of then-Gov. Mario Cuomo, was called in to help overhaul the commission, which had existed without much power. Hennessy asked Tom West, a young attorney who had worked with the Lake George Association, to help draft the new law.

The law, passed in 1987, gives the Park Commission extraordinary powers to regulate activity around the lake and on the water. The agency now polices the lake with its own marine patrol, issues boat permits and oversees docks, moorings and marinas.

The law also clearly says commissioners shall adopt “rules and regulations for the discharge of sewage.” But the Park Commission doesn’t have rules and regulations about sewage or even a sanitary inspector like Harry Smith to field complaints.

In West’s view, the Park Commission is failing to live up to the law and is ignoring science. He compared the failure to regulate septics to people’s failure to wear masks during the coronavirus pandemic.

“It’s time for the Park Commission to step up to the plate and take up the authority it was given back in the ’80s,” West said.

Legal challenges

It’s not as if the Park Commission hasn’t tried to deal with septic systems. It just hasn’t tried in a long time.

Soon after the 1987 law gave the agency its new power, commissioners set out to use it. But at nearly every turn, they faced a legal challenge of one kind or another, usually from conservative activists Bob Schulz or John Salvador, who both lived around the lake.

In court, the commission won some and lost some. One of its biggest losses was when Schulz challenged its 1990 plan to regulate septic systems.

A few communities, like the village of Lake George and the town of Hague, have sewer systems that collect wastewater from people’s homes and send it to a main treatment plant. Those are regulated by another arm of the state and subject to federal guidelines.

But many lake residents rely on septic tanks in their yards.

It’s easy to gloss over what the tanks do. Septics are really just a way to carefully dump sewage into the ground. The goal is that wastewater leaves a septic tank slowly enough that the soil near the home will remove the bad stuff before anything dangerous ends up in the lake. A broken septic system will release too much raw sewage too fast, overwhelming the soil’s cleaning power.

The Park Commission’s early septic rules were pretty straightforward: If someone had a septic system, they had to get it inspected to make sure the system was working and bad stuff wasn’t ending up in the lake.

For people who happened to live in areas where septics were more likely to fail because of things like poor soil, the rules created an out: The commission could consider plans to create a municipal sewer system to collect all that sewage and send it to a treatment plant.

But that was the rub. A large sewer system for the whole south end of the lake had been envisioned but failed to materialize a decade earlier amid local opposition. While sewer systems are usually considered a public good, they occasionally get attacked on the theory that they promote new development, which can be controversial.

Judges agreed with Schulz, who brought the case against the Park Commission: The agency hadn’t done enough to study the expansive sewer system that its septic regulations might lead to.

Instead of working to correct this relatively technical error by doing a study, the Park Commission gave up on septic inspections for the next quarter-century.

A known threat

Lake George’s problems were not only foreseeable but were also foreseen.

In October 1982, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency said that without better sanitation “existing water quality problems associated with the use of on-site septic systems in the Lake George Basin will continue and intensify.” In particular, the agency warned of algal blooms.

Fast-forward to 2018, the year after algal blooms marred Skaneateles Lake, the source of Syracuse’s drinking water and a lake similar in many ways to Lake George. Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s administration released plans to combat algal blooms on a dozen major New York lakes. Eleven of those already had documented blooms; the 12th was Lake George.

The report on Lake George, published by the state Department of Environmental Conservation, called for mandatory septic system inspections to start within three years, followed by money to help lakeside property owners upgrade failing septic systems.

Since that report, three years ago, there’s been little movement by the state to make that goal into a reality. And last fall’s algal blooms brought new scrutiny back on the state for appearing ready to break another commitment to do something about septics.

“New York State is committed to protecting the water quality of Lake George and waterbodies throughout the state and has invested record resources to ensure the protection of public health and the environment,” the department said in a statement.

In early December, a group of Assembly Point residents, led by Collins, wrote Cuomo a letter that asked what had happened to the 2018 goal of inspecting the lake’s septic systems.

The reply from Dave Wick, the Park Commission’s executive director, posed its own question: Inspections are easier said than done — and are they really even needed?

Wick, who grew up near the lake, has been his agency’s top staffer for nine years. He reports to a board. Many of the commission’s major decisions also get sent to Albany for approval.

Wick has taken an agency that fumbled early and often to one that seems to be carrying a few balls at once.

During his time there, the Park Commission began a boat inspection program to crack down on invasive species in the lake. Now, the agency is close to finalizing rules that update how close landowners can build to streams and what they must do to prevent pollution from running off their property.

The runoff rules, known as stormwater regulations, are, in Wick’s view, one of the keys to keeping the lake from deteriorating, because many studies find that stormwater is a bigger problem than septic leaks.

“So we’re doing very proactive good things,” he said, “but we can’t do everything at once.”

Wick said he’s not sure the science can justify what could be a multimillion-dollar septic inspection regime.

He is clear about what the problem is: The DEC oversees a handful of larger wastewater treatment plants around the lake. The state Department of Health has rules about new septic systems that go in the ground. But if a septic system is already in the ground, no state agency is in charge of making sure that septic system is functioning correctly.

The latest lakewide research doesn’t show that septics are the lake’s biggest problem, Wick said. One report he cites, a 2001 study, found leaking septics made only an “incremental contribution” to the lake’s problems.

The Assembly Point algal bloom was, in Wick’s view, minor, and nobody is sure yet what caused it. He doesn’t want the commission to overreact with rapid regulation that can’t pass muster in Albany or survive a court challenge.

Town of Queensbury Supervisor John Strough, however, is one of the local leaders around the lake who disagree. In the past several years, Queensbury and the town of Bolton adopted their own regulations to require inspections of septic systems before property can be sold. Queensbury property owners have to pay $250 for each inspection.

“The water quality adjacent to the home directly impacts the value of the home,” Strough said.

What Queensbury is finding shows a “great need” for a lakewide inspection program, he said. Though many of the problems were minor, about 80 percent of the systems inspected so far in Queensbury have at least some sort of problem that required repair.

Across New York, other water managers have decided septic regulations are worth it. Routine septic inspections are mandatory for people living around Keuka Lake, Otsego Lake and Cayuga Lake, for instance. And New York City even helps pay for people in the Catskills to upgrade their septics in order to keep leaks from polluting the city’s water supply.

A new septic system can cost $30,000, which is surely why there is hesitation to make people deal with failing septics on their own. Last year, the Fund for Lake George worked with two banks to offer special loans to upgrade septic systems that are leaking sewage into the lake. The DEC’s plan for the lake said if there is an inspection program, the state should help pay to repair failing septic systems.

Wick argues that regulating the wrong way, without proving to people and agencies that it’s needed, could complicate future efforts to confront pollution.

Collins agreed that it’s hard to prove that an algal bloom is caused by a septic leak. Still, she said, years of research, in New York and across the globe, have made a connection that demands action. Regulating septics is a start.

“You control what you can control,” she said.

Ry Rivard covers water policy for the Adirondack Explorer, a nonprofit news outlet covering issues within the forest preserve.

Comments are closed.