Aging water infrastructure requires constant attention and investment to keep everyone safe – especially if the US is to avoid another Flint water crisis. According to the Environmental Protection Agency, water utilities should invest more than $ 300 billion over the next two decades to renew and improve their networks of utility lines and underground pipes, many of which contain lead. This is partly because the health effects of lead exposure are so severe: even low levels can cause irreversible neurological damage.

Eliminating lead pipes across the country is the ultimate goal, but the standard practice of many utility companies makes it extraordinarily difficult. Utilities generally consider pipes owned by customers on private land – so they often don’t use government or utility funds to replace them. Instead, they will choose to only replace the portion of the system on public land, unless homeowners voluntarily pay to replace service lines on their properties. If property owners fail to sign up, the lead service line is only partially replaced – and this ultimately results in a limited or long-term reduction in exposure risk. In fact, it can increase the chance of lead getting into drinking water in the short term.

As a result of this approach, low-income paint communities in their neighborhoods can see much more spotty replacement rates – in large part because owners in those areas are unwilling or simply unable to bear the significant cost of a full service replacement are lines.

“If a program primarily benefits those who have money, you have an environmental justice issue,” said Tom Neltner, director of chemicals policy for the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF). “We have to make sure that all residents, regardless of how much money they make or what skin color they are, benefit from these rules to protect people and public health.”

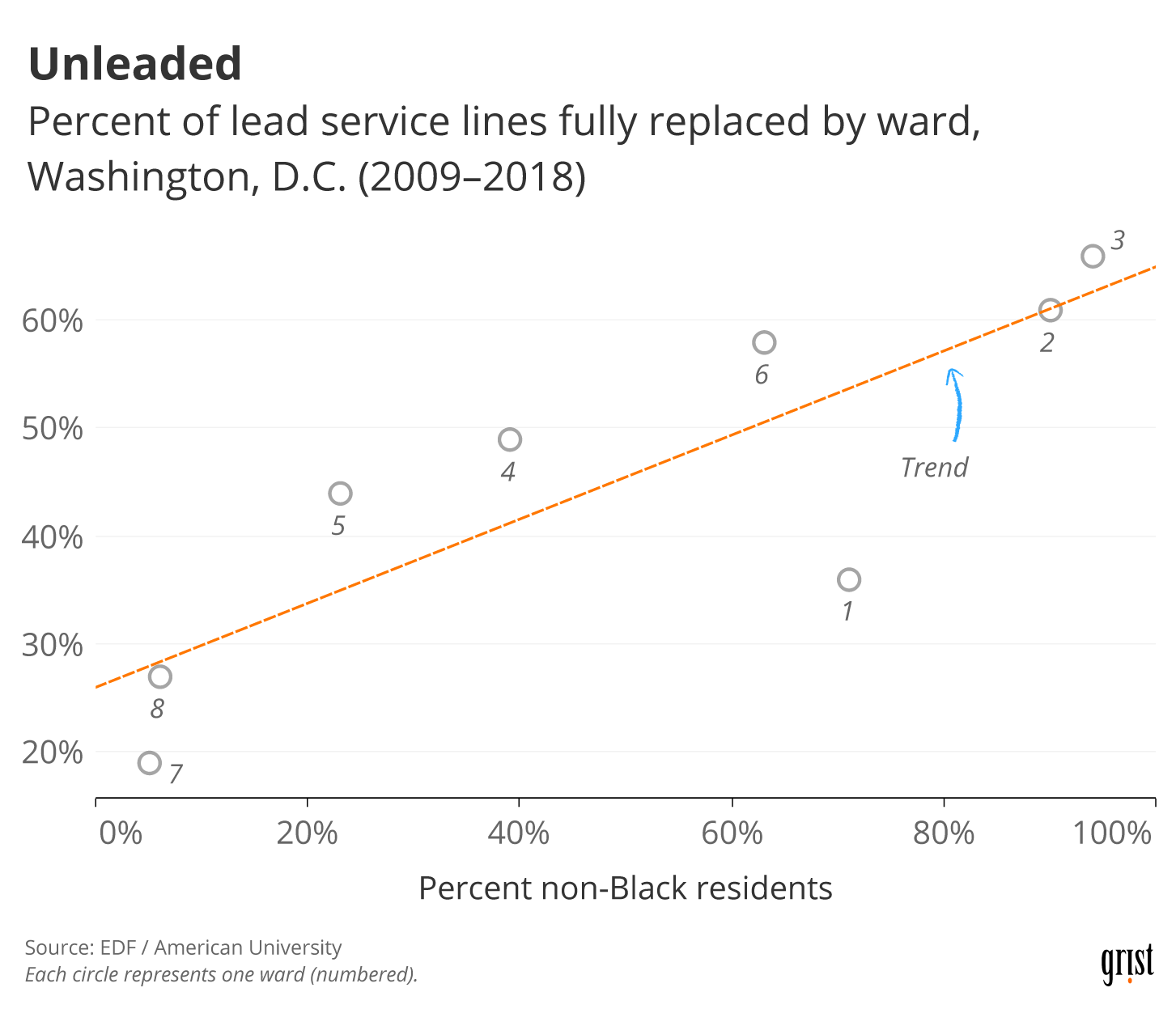

A new report from the EDF and the American University’s Center for Environmental Policy confirms this. The researchers analyzed more than 3,400 replacement leads for lead service lines in Washington, DC that occurred between 2009 and 2018. During this 10 year period, the local water company only covered the cost of replacing lead service lines on public land, which customers had to pay for. The rest of the service is on private land.

After a cross-examination of the population structure of the city and the participation rate of those who had chosen to cover the service costs, the researchers found large differences between predominantly low-income African American households and more affluent white households. Department 3 of the city, where the median household income is $ 107,499 and a vast majority of residents do not identify themselves as Black or African American, the rate of customer-initiated lead service line lines was highest. Meanwhile, Districts 7 and 8, both mostly low-income black neighborhoods, had the lowest service replacement rates.

Clayton Aldern / Grist

“Washington DC has been very aggressive in a good way to make it easier for residents to participate,” said Neltner. “But the numbers showed us results of unintended consequence – where people with money went to the program and those without, didn’t.”

The analysis also shows that the Trump administration’s recent proposed changes to the lead and copper rule would increase the financial burden on low-income paint communities by continuing the existing surrogate paradigm where utilities are only responsible for replacing lead pipes on public property are .

“We work closely with utility companies across the country. They need to find a way to get out of this paradigm where residents are fully responsible for paying for private property replacement,” said Neltner. “I want them to look and say, ‘We have to do this not only for the benefit of public health, but also for the sake of environmental justice.'”

To date, Madison, Wisconsin, and Lansing, Michigan are the only major cities ahead of the curve as all of the aging lead service lines have been successfully removed. It wasn’t easy for Madison, but after court hearings and public battles, officials finally launched an ambitious program in 2000 to replace every single leadership in the city. Lansing, Michigan followed suit, removing its last lead water line in 2016. After what happened in Flint, Michigan, many other cities are also moving faster towards the same goal of eliminating lead-based pipes.

Last year Washington, DC, passed a new law banning the partial replacement of lead service lines during infrastructure projects and emergency repairs. In these cases, the owners no longer have to bear the costs. The directive also changes the previous provisions by providing funding to homeowners who were unable to replace their pipes under the old directive.

“It will take a while, but we need every opportunity to completely replace these lines,” said Neltner. “Once you realize that lead pipes are a significant source of health risks for children and adults, you realize that you need to get them out of the ground.”

Comments are closed.